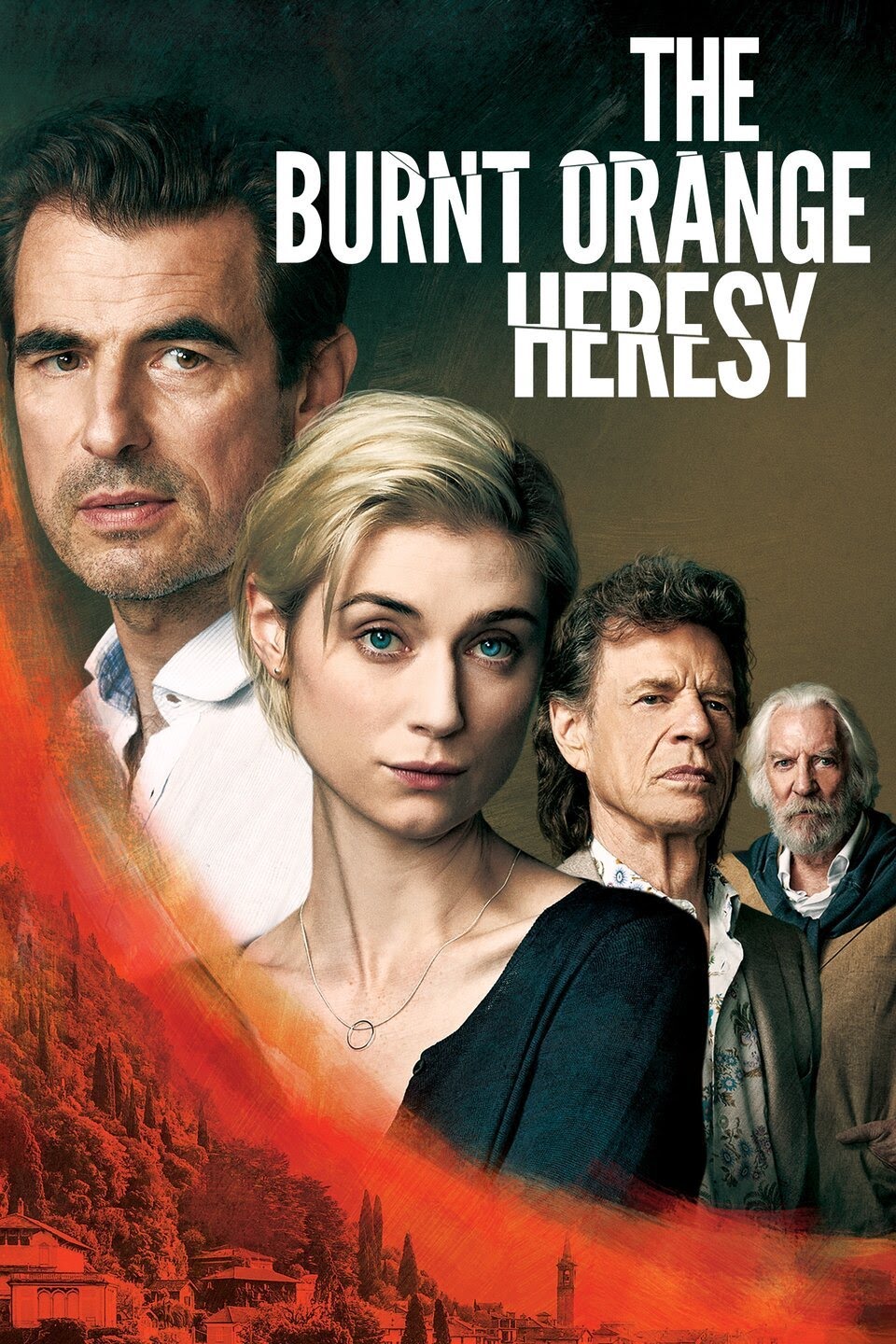

The title of a film — or any piece of art, for that matter — can carry a lot of meaning, hidden or otherwise. A title can also mean nothing at all, beyond a method used to catch your attention. It’s not often, however, that a film is as perfectly reflected in its title as The Burnt Orange Heresy, a phrase that sounds essential and poetic, but ultimately means nothing at all. The Burnt Orange Heresy follows art critic James Figueras (Claes Bang) who takes his job more seriously than every other aspect of his life, including his own morality. Joined by a young American woman (Elizabeth Debicki), Figueras travels to the Italian countryside to spend the weekend with an eccentric art dealer (Mick Jagger). Living on the dealer’s property is the iconic and elusive painter Jerome Debney (Donald Sutherland), whose entire catalog has been destroyed in various accidents over the years. Figueras is tasked with stealing a piece from Debney’s studio and the weekend spirals into a greed-induced quest for power.

Without sharing too much about the plot itself, the film is a tug-of-war between the ideals of Figueras and Debney. Figueras, the critic, believes that the beauty of any piece is in the story you can construct around it, whether that narrative carries truth or not. Debney, the artist, finds the critics comical, as they pull some sort of secret code from every brushstroke when, in reality, it’s never intended to be that complicated.

The nature of that debate is summed up perfectly within the title, “The Burnt Orange Heresy.” In the film, it’s the name of one of Debney’s pieces. When asked about its meaning, he simply says that it’s nothing more than a phrase that sounds like something great, when really it means nothing at all.

The idea here is great, but it also holds the film back from being something much greater. Director Giuseppe Capotondi and screenwriter Scott B. Smith think themselves the Debney of this scenario, but they’re actually Figueras. The Burnt Orange Heresy is so hell-bent on telling the audience what art is that it forgets it’s supposed to be creating art in the process. What we’re left with is a lot of big thoughts unceremoniously crammed into a box that’s way too small to fit them comfortably in.

Fortunately, Capotondi’s technical skill, combined with the mystifying performances of his leads, makes the box rather enjoyable in its own right. Watching Figueras spiral into his own madness is a thrill from start to finish, while Debicki is flawless as his foil. While this character may seem more cut-and-dry than others she’s played in the past, Debicki transforms herself into something as fascinating as it is heartbreaking.

The third act of Heresy is where the film really shines, despite its insistence on driving home an ultimately meaningless metaphor with little care as to just how hard you’re being beaten over the head with it. The finale is a well-executed one, otherwise, designed to keep you on the edge of your seat and succeeding in doing just that. If you can get over the fact that The Burnt Orange Heresy tries entirely too hard to make you love it, you’ll find that there really is quite a bit to like.