We know for a fact that life can exist on planets that orbit yellow dwarf stars like our sun and are optimistic about the chances for smaller red dwarf systems like Trappist-1. When it comes to their awkward brown dwarf cousins, however, astronomers don’t think life is possible — they’re too small and cool to support it. So it’s a bit of a bummer that astronomers have discovered as many as 100 billion brown dwarfs in our galaxy, out of a maximum 400 billion stars in total.

We know for a fact that life can exist on planets that orbit yellow dwarf stars like our sun and are optimistic about the chances for smaller red dwarf systems like Trappist-1. When it comes to their awkward brown dwarf cousins, however, astronomers don’t think life is possible — they’re too small and cool to support it. So it’s a bit of a bummer that astronomers have discovered as many as 100 billion brown dwarfs in our galaxy, out of a maximum 400 billion stars in total.

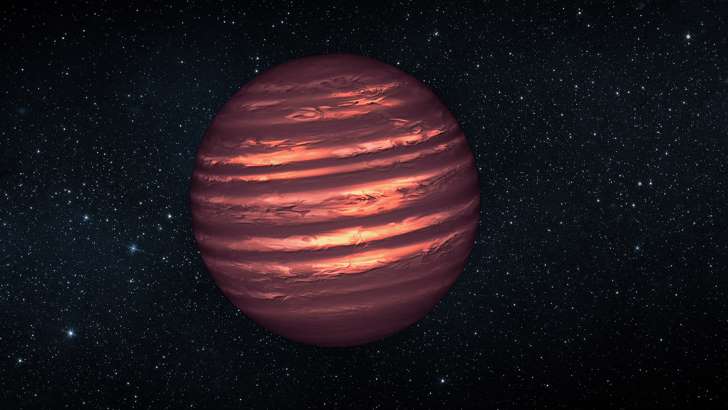

Brown dwarfs are too hot and big to be planets, but don’t quite qualify as stars because they don’t have enough mass to fuse hydrogen to helium in a “main sequence” reaction. It’s thought that they glow and emit infrared light, plus a very small amount of visible light, thanks to less energetic fusion of deuterium (2H) or lithium, provided their mass is above a certain threshhold. Because they can’t sustain a stable fusion reaction, they’re referred to as “failed” stars.

Despite the lack of opportunity for life, the discovery is still exciting. Astronomers always thought that brown dwarf stars were out there, but never actually imaged one until 1994, once infrared imaging tech improved for ground-based telescopes. By 2013, scientists had imaged thousands of them using the Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes, and got an inkling that there are many more than previously thought — possibly up to 70 billion in our Milky Way galaxy.

Astronomers from the University of Hull, thought that figure seemed high, so they scanned a young, massive cluster 5,000 light years away using the Very Large Telescope. Surprisingly, they discovered that the density of brown dwarfs could be even higher, meaning there could be up to 100 billion of them in the galaxy. That’s a lot, because researchers think our galaxy only holds up to 100 billion to 400 billion stars of all types, total.

The study has yet to be peer-approved, and makes a few assumptions, but other researchers that have checked the data think it’s plausible. For one thing, small celestial objects are much more common in the universe than large ones — the most prevalent type of star in the Milky Way, by far, is the tiny Red Dwarf like the one that powers Trappist-1.

So what does that mean? As mentioned, it’s not a good sign for life, as brown star systems are unlikely to support it, so many fewer stars than thought could host life. On the other hand, the discovery could help explain some (but not nearly all) of the missing matter in the universe, helping scientists working on the dark matter puzzle.